From Two to Three: An Essay by David b. Auerbach on London and Wen-Ying Tsai

From Two to Three

An Essay by David B. Auerbach on London and Wen-Ying Tsai

Wen-Ying Tsai pioneered what he termed “Tsaibernetic” sculpture. His son, London Tsai, grapples with his legacy in the new work of this exhibit. These cybernetic works are responsive to their surroundings, and specifically to viewers, artworks possessed of a dynamism that both accommodates and copes with change. That is, at least on a surface level, what cybernetic sculpture seems to be. But the greater meaning of cybernetic sculpture (and cybernetic art more generally) is more than a matter of reactivity. It is an avenue for exploring the human in art.

The word cybernetics comes from the Greek κυβερ (kyber), a word meaning governance, control, and steering. For Norbert Wiener, who popularized the term, the crux of cybernetics was the study of the control and communication of a wide variety of systems, from human societies to robotics to the brain. Cybernetics encompassed biology, primitive robots, neuroscience, and political science in its sweep.

The iconic representation of a cybernetic organism is a thermostat. Its sensors take in its surroundings in exactly one linear aspect. The control mechanism seeks to reestablish homeostasis by turning cooling and heating systems on and off. The mechanism isn’t purely reactive, however. There is some hysteresis built into most thermostats so that it doesn’t flip the heating system off and on every time the temperature rises or falls past a single point. Already, homeostasis becomes a more complicated matter in this most simple of systems.

In their feedback-driven responsiveness, the Tsais’ sculptures function as cybernetic organisms akin to any other (whether a person, an amoeba, or a thermostat), less an object than a system, operating by laws and regulatory mechanisms that can be captured mathematically. But to what end? To put it more clearly, what does it mean to repurpose the diagnostic goal-oriented theory of cybernetics for aesthetic purposes? Cybernetics treats an organism as a purposeful entity in a greater environment, whether that purpose is to regulate temperature, operate heavy machinery, or most often, to simply survive. But a work of art is meant to exist for aesthetic purposes. To put it bluntly, it is supposed to sit there and be enjoyed, in the broadest possible meaning of the term “enjoy.” If an artwork is cybernetic, what is being controlled, who is controlling it, and what even is the organism?

I suggest there is not a single answer to this question, but several, on different levels. Vilém Flusser provides us with one. In his piece “Tsai,” Flusser incisively attempted to describe Wen-Ying Tsai’s cybernetic art as deploying an intensely human playfulness:

Tsai's quasi-animated objects are true attempts in the direction of creation of life (much truer than are the parallel attempts made by biologists and cyberneticians), because they are artistic...Animate objects would certainly give our situation a completely different climate. They would not react to our acts, but would respond to them.

For Flusser, the ludic, aesthetic joy of such a work mitigated against the sterile, anti-human tendencies of science and technology, even under cybernetics.

Yet there is another possible level of cybernetic analysis missing from Flusser’s evaluation, however, one brought to light in London Tsai’s work. Flusser’s portrait of the elder Tsai’s work separates the art from the artist: the former is shaped and determined by the latter, but the artist’s vision is determinate and unquestioned. The relation of art and artist, in Fluser’s analysis, is not presented in cybernetic terms.

London Tsai’s work, however, suggests that it should be. When London Tsai describes the construction of one of his earlier, non-cybernetic sculptures, “Mobile Fortune Cookie,” he chronicles the struggle of hammering metal to achieve the desired shape:

London Tsai, Aura Rediscovered, 24” x 24” x 6”, 2022

The slightest change in one region immediately resonated throughout. The ensuing battle is what I called “chasing the panels.” When I find myself in this fray, I enter into an automatic state of mind where I move from part to part resolving singular tension spikes, introducing others, which means going round and round until all the problems are within my acceptable thresholds. When I am in that zone of action, I am unaware of time and hours pass quickly. I remember that night vividly because in my heightened state of awareness, I had the strange feeling that I was my father. I essentially faced the same challenges that he had faced in his artistic career where resolving one problem in his kinetic sculpture introduced other problems elsewhere–the same phenomenon of multiplying perturbations. Although I understand what’s happening locally, the global situation seems to be elusive; only by zipping back-and-forth all over the surface can I hope to settle things.

While the sculpture itself is not cybernetic, what Tsai here describes is the very essence of a cybernetic process: the integration of local manipulations into a stable, goal-oriented process. Even the language of thresholds and perturbations echoes that of classical cybernetic theorists from Wiener to W. Ross Ashby to William Grey Walter. The goal, however, is one of aesthetic creation rather than governance per se. The artist and sculpture become a single organism tasked with reaching the ideal state of actualizing the artist’s intent. Yet the intent is not the undisputed controlling force, but one input into a complex cybernetic process.

From here we can see a potential passageway from sculpting-as-cybernetic-process to cybernetic sculpture itself: it is taking such a process as Tsai describes and adding in the viewer, so that the viewer is not interacting with an autonomous object such as Flusser describes (one birthed by the artist), but that the viewer, artwork, and artist are forming a coherent cybernetic triad, rather than the viewer-artwork dyad Flusser observed in Wen-Ying Tsai’s work. This shift is illustrated in London Tsai’s “Aura Rediscovered,” a light box with an image of “Mobile Fortune Cookie” itself, illuminating itself in response to a viewer’s approach (and dimming on departure), as if in an echo of London Tsai’s own engagement during the creation of “Mobile Fortune Cookie.”

That shift from two (artwork and viewer) to three (artwork, viewer, and artist) is London Tsai’s leap. In mechanical systems, a two-body dynamic system is closed, admitting simple solutions, while three-and-greater-bodied (n-bodied) systems of more than three objects will usually fall into chaos, richer yet evading elegant mathematical description. To use the language of cybernetics, one can say that greater-bodied systems do not obviously appear to tend toward homeostasis, even though they can display homeostasis at a higher, more generalized level of description. An individual neuron or even a section of a brain may not always tend strictly toward homeostasis, but they can nonetheless serve as a means to a greater organism (a human, an animal) maintaining a higher-level homeostasis.

Tsai himself is not as sanguine about the virtues of homeostasis. In conversation, London Tsai told me that while his father’s work sought to reassert an almost utopian stability in the face of viewer intervention, his own work attempts to be more reactive and responsive to it, replacing stability with a kind of accommodation. It is far more sanguine with regard to the liquidity of roles between creator and viewer. We could say, then, that London Tsai’s work sacrifices a controlled and knowable homeostasis in a more tentative but vaster search for a higher-order form of homeostasis, one based in more complex systems that do not admit of simple mathematical descriptions. This movement parallels that of post-cybernetic theory itself (whether complexity theory, artificial intelligence, or systems theory), in which there has been a slow progression away from a more naive and audacious attempt at control (what political scientist James C. Scott contentiously describes as a “high modernist” orientation of top-down projects like Brasilia, as well as the truncated attempts of the Allende government to establish cybernetic governance in Chile in the early 1970s) and toward a serious and frequently frustrated attempt to come to terms with the resistance of systems to easy cybernetic description and control.

The third body need not be the viewer. London Tsai’s new works are premised on a fundamental engagement in the most intimate of realms, that of family. Whether one chooses to see his father as co-creator, influence, or interrogator, London Tsai’s art represents that greater n-bodied complexity even before it engages the viewer, on account of the deep presence of his father and his father’s artworks during the creation of his own. This, I want to suggest, is yet again an attempt at reaching for a higher and more profound homeostasis at the cost of abandoning a lower-level state of homeostasis. It is the next step of development after the revolutionary groundwork of Wen-Ying Tsai’s original sculptures, one more fraught but also potentially far richer.

For Flusser, Wen-Ying Tsai’s works evaded the reductionistic risks of cybernetics through their aesthetic and ludic orientation. With his pioneering works now decades behind us, however, we can also see that that playfulness itself was strictly demarcated by a singular artistic vision that prescribed a similarly singular experience. London Tsai’s work sacrifices that determination and certainty for ambiguity and wonder, but that sacrifice is revelatory.

David B. Auerbach is a writer, technologist, and software engineer who worked at Google and Microsoft after graduating from Yale University. His writing has appeared in the Times Literary Supplement, MIT Technology Review, the Nation, n+1, Tablet, The Daily Beast, and Book forum, among many other publications. He has lectured around the world on technology, literature, and philosophy and has done scholarly research on James Joyce, William Shakespeare, and artificial intelligence. His first book, Bitwise: A Life in Code, was published by Pantheon in 2018, and his book Meganets: How Digital Forces Beyond Our Control Are Commandeering Our Daily Lives and Inner Realities will be published by PublicAffairs in 2023.

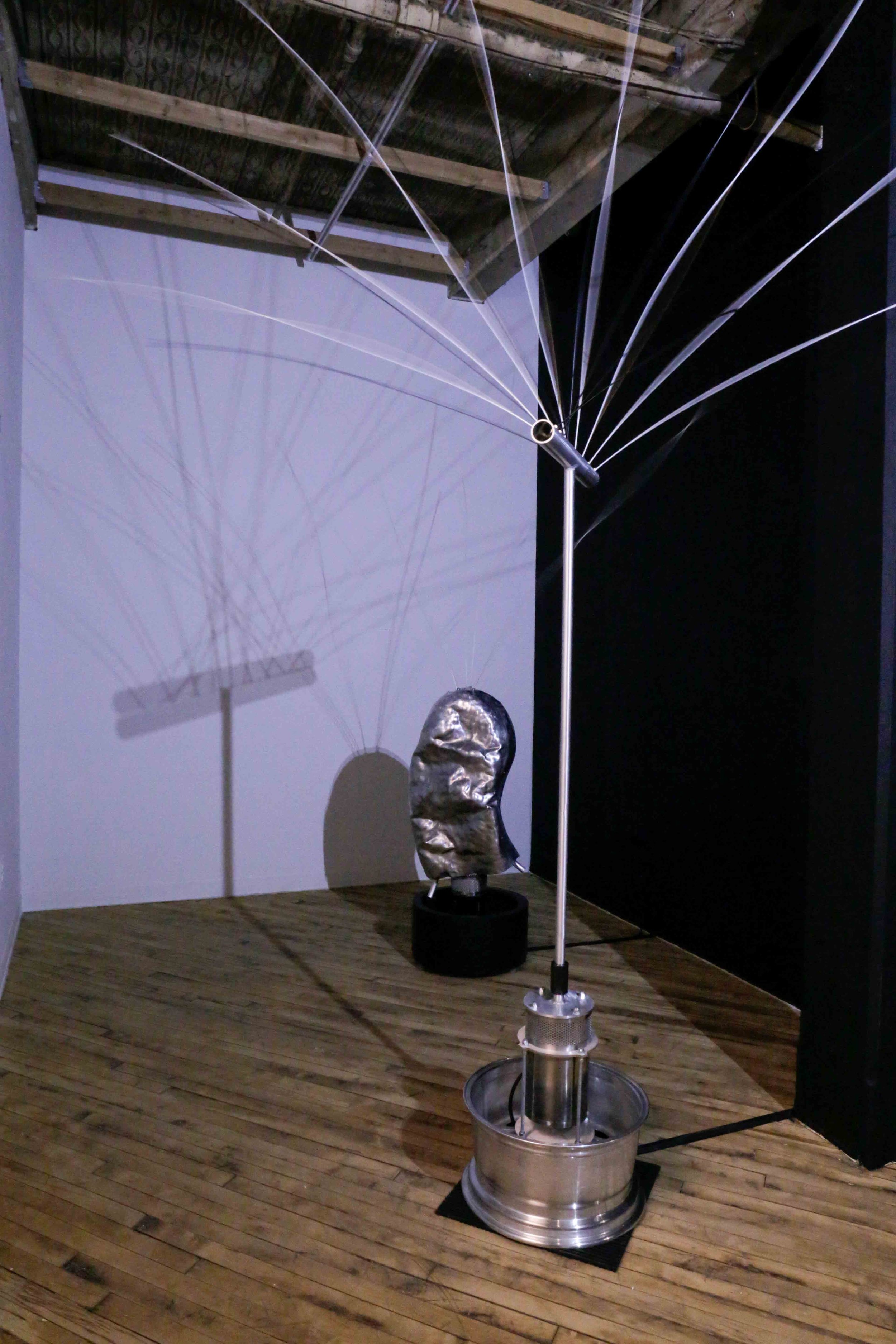

London Tsai (b. 1970) is an American artist known for mathematically-inspired paintings and sculptures, the latter composed of shaped and welded aluminum sheet, TIG-welded tubular structures, and since 2017, as an extension of his father’s practice, digitally-controlled motors, LED strobe lights, and arduino-controlled feedback systems. London Tsai was born in Cambridge, MA and grew up in Paris and New York. He received his BS in math from Tufts University and his MA from the University of Pittsburgh.

Wen-Ying Tsai (1928–2013) was an American sculptor and artist best known for creating sculptures using electric motors, stainless steel rods, stroboscopic light, and audio feedback control. Wen-Ying Tsai was born in Xiamen, China and emigrated to the United States in 1950, where he attended the University of Michigan, receiving a B.S.M.E. in 1953. He moved to New York City after graduation and embarked on a successful career as an architectural engineer. In 1963, Tsai won a John Hay Whitney Fellowship for Painting, after which he decided to leave engineering and devote himself full-time to the arts. In the following decade, Tsai created his seminal cybernetic works, which he continued to develop in myriad directions until his passing.