It's the In Between We're Concerned With: Finding Hypertopia in David Herbert's Hand-Me-Down, Written by Morgan Joseph Hamilton, Ph.D. Candidate

It's the In Between We're Concerned With

Finding Hypertopia in David Herbert's Hand-Me-Down

Written by Morgan Joseph Hamilton, Ph.D. Candidate

It's the In Between We're Concerned With

Finding Hypertopia in David Herbert's Hand-Me-Down

Written by Morgan Joseph Hamilton, Ph.D. Candidate

Can you feel the barrier between You and the infinite Universe that is not You? If you could feel that barrier, could you cross it? Or would that ‘crossing’ merely push the borders of You into the infinite Universe? Since ‘crossing’ is only pushing You further into the infinite Universe (andif we agree the infinite Universe is very much not You), then space is either You, the infinite Universe, or both. If space represents the absence of You in the infinite Universal whole, then there is no space between where You are and where you are. This pedantic exercise is meaningless in the face of experiencing a physical world where You are no more you than the infinite Universal whole you are a part of.

What does the edge of You (or anything for that matter) look like? Deleuze and Guattari's (1980) metaphysical jaunts of edge-finding and edge-denying play at a resolution. Do You end at the outside of your skin? What of the microscopic flakes that brush off your skin? What of the fact that You exist in the hearts of loved ones? Where You end and space begins is irrelevant, what matters to me and You is who drew that edge and for what purpose? When power hoarders define personhood for us (the youness in non-you space), existence is political. Being a political being turns the edges of a natural entity into a controlled border (and borders do a lot of heavy lifting in the imagined communities they define). The border of You is a site of tension that ripples through our understanding of what it is to be in the Universal whole. Art is an action that doubtingly fingers the space between being and not being, between You and everything else, between definition and liberation. We often accept the narratives we’re given at the thresholds of museums and galleries that chant “This is Art and that is not!” In David Herbert’s case, it’s the in between we’re concerned with.

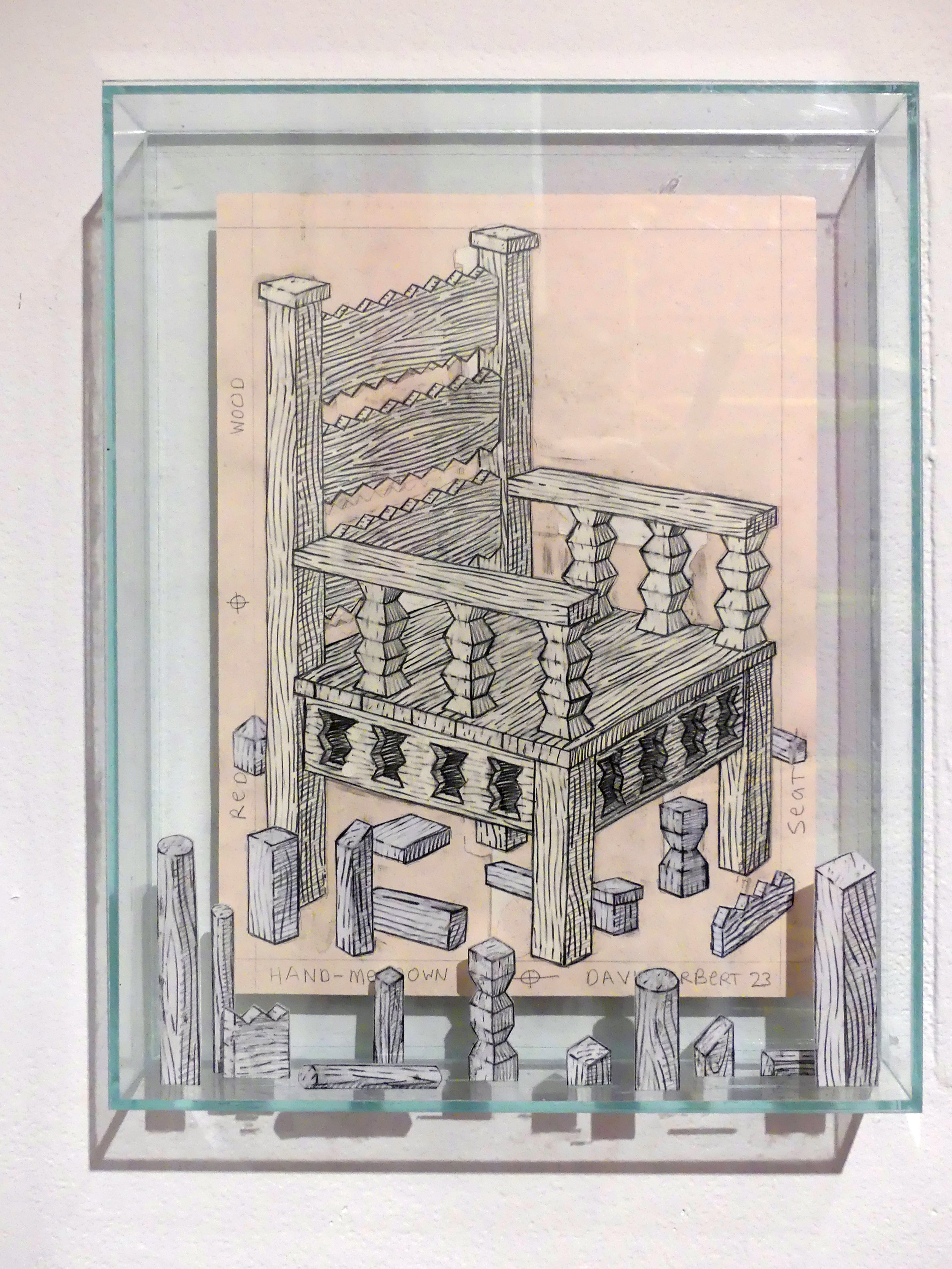

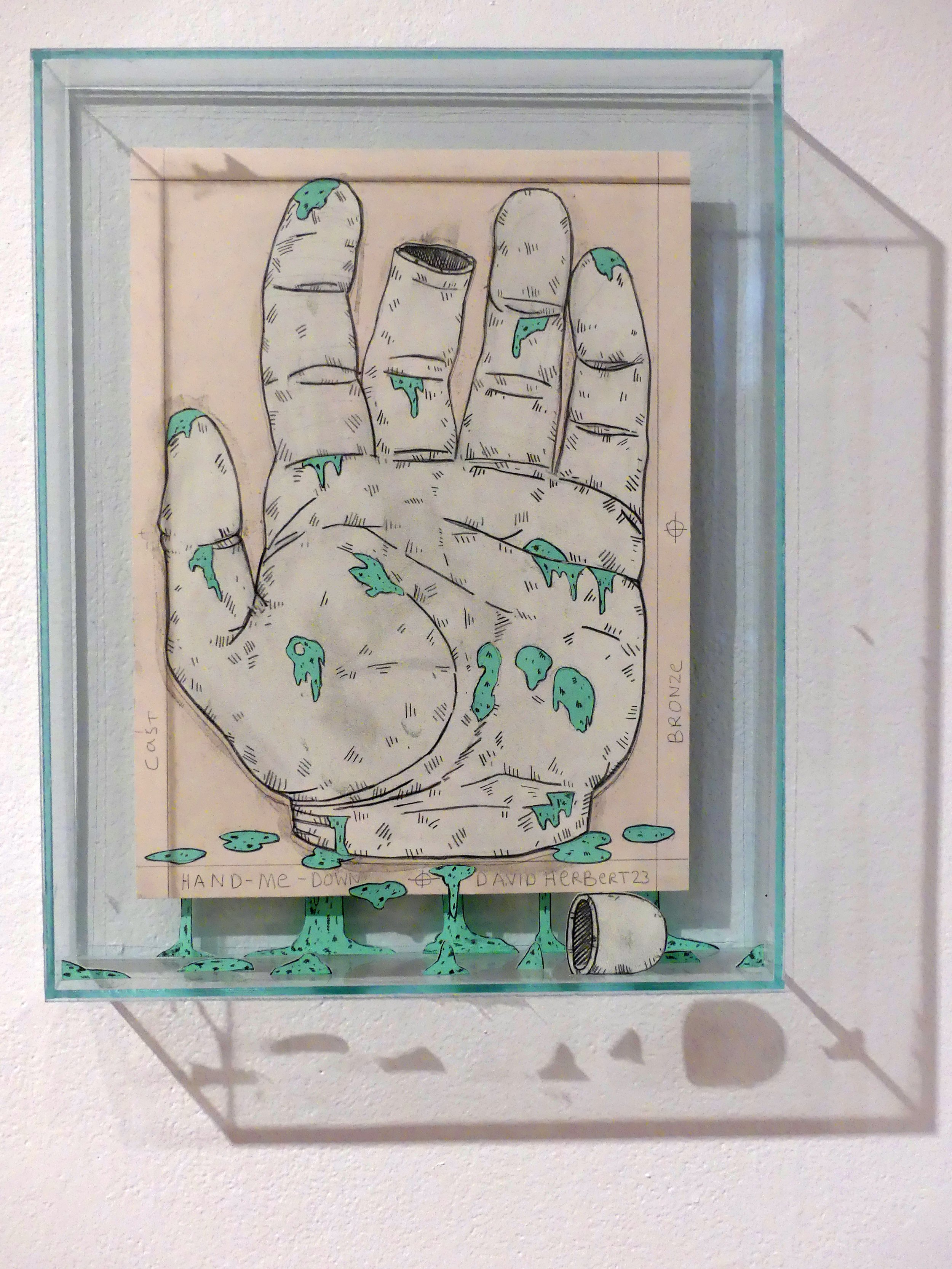

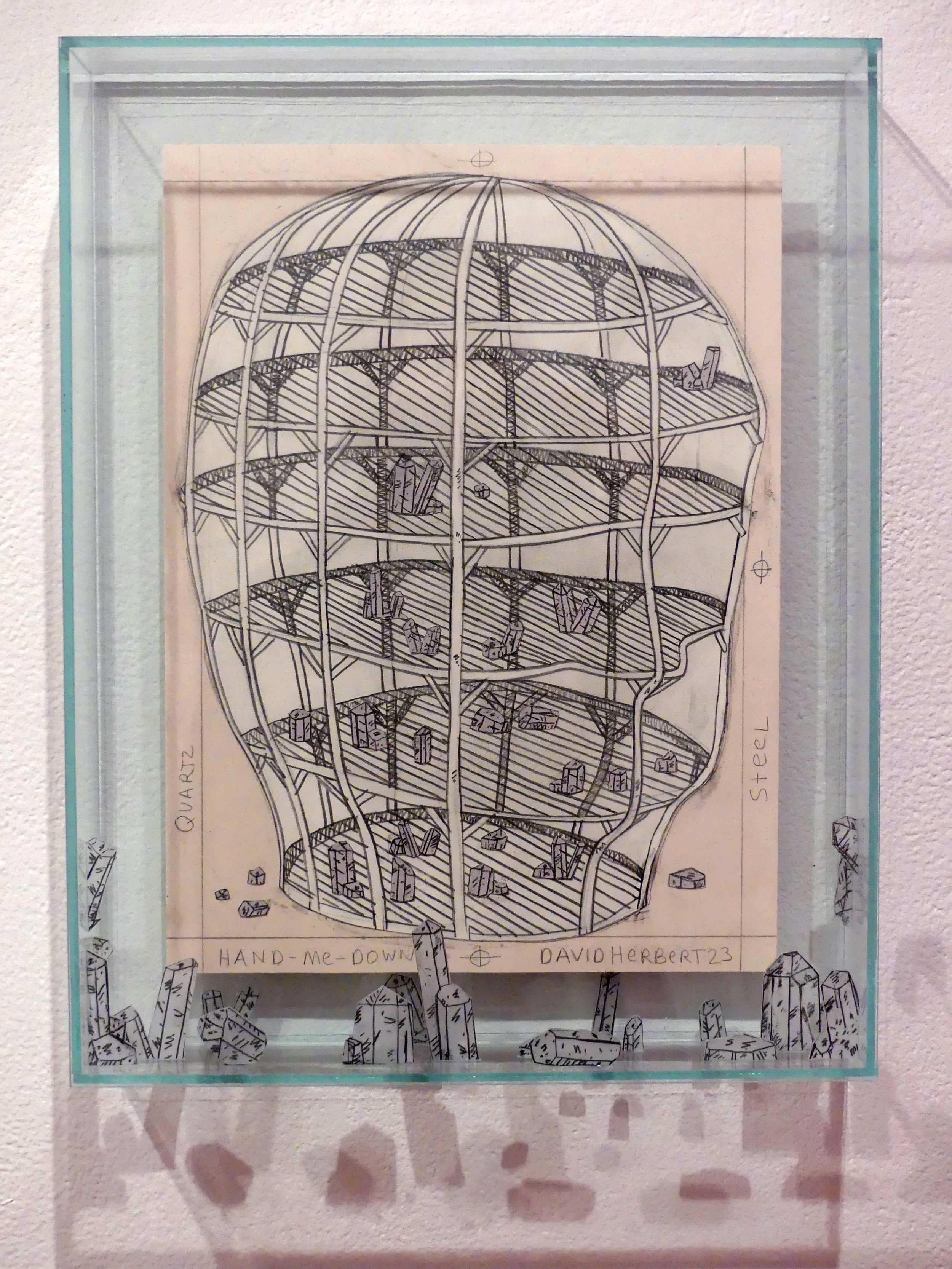

I question the edgy-ness of things as I experience seeing David Herbert’s Hand-Me-Down at Grizzly Grizzly in Philadelphia. His installation is singular and engulfs you; it welcomes you in and slams the door closed behind you. Each work, the whole room really, begs the question: where does artwork end and art space begin? Herbert sculpts the metaphorical distance between two cities, Paris and Philadelphia, by calling on ancient and modern art, fused by Memphis colors and textures on Euclidean shapes. Grizzly Grizzly, a gallery no larger than 200 square feet, is made ever smaller by the site-specific construction of a pink wall; a gridded barrier defining what is to be seen (and how it is to be seen) and what is not. Herbert’s choice to shrink the space puzzled and intrigued me. Removing a volume of the gallery renegotiated the space that his sculptures and drawings existed in. A space that no longer belonged to Grizzly Grizzly, nor you and me, but to the artwork. When artwork becomes art space, the everything-in-between-ness expands from floor to ceiling.

Museums and galleries are examples of what Michel Foucault (1986) called heterotopia, the third (and most achievable) sibling of Utopia and Dystopia. If Utopia is “not a place”, heterotopia is “all places at once”. Think of heterotopia as a site where all other things are possible simultaneously (i.e. a movie theater, a botanical garden, an aquarium, an museum). In what other reality could you see a Brancusi bronze near an Egyptian sarcophagus as in The Met? Distances of geography and time are collapsed. Heterotopia describes a world where all other things combine to create a new space of endless possibility. The turbulent travel from one gallery to the next (e.g. one era to another) in museums is smoothed by heterotopic understanding. Walking from a room of Greek and Roman artifacts to a room of European decorative arts is no more taxing on us than changing channels, or swiping to the next TikTok. The hallways and corridors are physical manifestations of the static glitch between channels (or WiFi buffering).

We are primed for the whiplash of simultaneity in our culture, itself a product of globalized consumerism. Neil Postman (1984) expounds on this in his book Amusing Ourselves to Death, where he details mass communication’s role in mainstreaming heterotopia. Perhaps with a wry wink at Monty Python’s And Now for Something Completely Different (1971), Postman articulates how the ubiquity of news anchors’ “and now… this” introduced us to a barrage of unrelated topics unified by what media companies deem important. Herbert acknowledges how art spaces collapse time and place and recreate (or reinforce) the “and now… this”-ness of art experiences. In one room, he combines the world out there and a world of his own, we are invited to view it, but he knows we’ll never see it as he does.

The work Herbert does is mostly unseen. He collapses the dimension between references of time, culture, and space. He is hyperlinking in real time (when you click a link, it takes you to the reference in an instant). You aren’t meant to witness the centuries of scientific understanding that led Tim Berners Lee to ditch file directories and make words responsive, you simply click and you’re there. Lee and his colleagues developed hypertext, text bridging points within an entity non sequentially. Is that not what I’ve described in so many words? Hyperspace is something that is or exists in a space of more than three dimensions. The prefix haunts me as I dig deeper into its contemporary uses, it serves so many things Herbert’s exhibit elicits. This article is hyperlinking from my perception of the exhibit to the myriad connections I make in my own experience. If heterotopia is “all other places”, then hypertopia is “the beyond place”, or “the place between”. Hypertopia exists in the non-physical aspects of mass communication’s “and now… this”-ing of the Internet. Hypertopia exists within us. It is the moment of connection when we enter an art gallery and see fantastical new things. Hypertopia is to traversing incongruous things as hypertext is to linking pages online. Foucault’s (1986) heterotopia necessitates the rooms within rooms, the picture of the maquette of Herbert’s exhibit looks into the room that holds the picture of the maquette of Herbert’s exhibit. The recursive turtles-all-the-way-down-ness of Herbert’s creation is itself only one atom of his lived experience. All atoms or unclefts of his life-as-experience come together to tell a story to himself about himself. The narrative thread connects everything, from a candy wrapper on the street to god itself. Theorist Jane Bennett breathed life into new materialism in Vibrant Matter (2010) arguing for the vital life force of everyday objects. Gutter trash is as much a part of the human story as grand creation myths. If everything is vibrant matter in a simulation of itself, how do we know what is special, what is Art? I’ll offer a cliché: it’s in the eye of the beholding.

Through personal thoughts, doubts, revelations in a context that typically privileges refinement and rigor, I review the list of links at the top as a very narrow set of connections. Though a participant in pop culture, to what and how I make sense of the exhibition is uniquely me. I enjoy the gut reactions to art in art spaces, I rely on the entire experience of seeing art. It doesn't always begin in the parking lot, but this time it did. Where do I even draw the line between “seeing David Herbert’s new exhibit at Grizzly Grizzly” and “not seeing David Herbert’s new exhibit at Grizzly Grizzly”? As I write this, I am in a mental recreation of the gallery, perusing my memory of the artworks. In a way I am more there than when I was actually there. Many of us make immediate connections to our lives when we see new things. We construct our understanding of the world, and no two minds see the world in the same way. Herbert’s Hand-Me-Down creates a brand new space never before seen and never seen again in the existence of the infinite Universal whole. What is left is changed and contextless, floating in a worldview of our own making. Herbert looks at artworks and artists as legacies handed down through generations and has to decide what they mean for himself, he begs us to do the same.