Leah Modigliani: Art as Palimpsest, an Essay by Ksenia Nouril

Leah Modigliani: Art as Palimpsest

An Essay by Ksenia Nouril

Back in March, at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, Grizzly Grizzly premiered Rome, 1947, a much anticipated solo exhibition by Leah Modigliani. Her new work was made in response to our contemporary political climate to be exhibited in the midst of the democratic primaries in this important election year. In this coinciding essay, Ksenia Nouril, The Print Center’s Jensen Bryan Curator, examines the underpinnings, histories, and connections at play in Modigliani’s work, while also adeptly adjusting her lens to adapt to the unforeseen changes that have upended our lives in ways that would have been unknowable just a few short months ago.

2020 programming is supported by Added Velocity which is administered by Temple Contemporary at Tyler School of Art and Architecture, Temple University and funded by the William Penn Foundation.

Leah Modigliani: Art as Palimpsest

Let me begin rather unconventionally by stating that I’ve written this essay thrice due to the rapidly changing circumstances of everyday life in 2020. What began as a standard prompt to write about an artist’s work developed into a much deeper and more emotional consideration of how that work mirrors society. By admitting the intimate details of my circuitous journey, I am following the advice of the artist Leah Modigliani herself, who writes, “THE TRUE CRITIC knows that the most effective criticism is grounded in the confidence of self-exposure and self-criticism, not in the seemingly objective mastery of facts.”[1]

A Critic’s Manifesto: Exposure

Newsprint, 2020

This dictum begins Modigliani’s manifesto enumerating thirty-one qualities of a “true” critic. Printed as a one-sided broadsheet on newsprint and released in March 2020 at the opening of her Grizzly Grizzly solo exhibition, A Critic’s Manifesto: Exposure gestures to precedents in the historical avant-garde, namely Filippo Tommaso Marinetti’s Manifesto of Futurism, which was published on the front page of the French newspaper Le Figaro in 1909. Whereas Marinetti projects the errant machismo of interwar fascism, Modigliani promotes self-reflexive non-aggression through concerted acts of thoughtfulness: “The true critic understands that criticism is an ethics of care that can only emerge out of a great love of her subject.” Written from the perspective of a woman, it joins a rich tradition of feminist manifestos, like Mierle Laderman Ukeles’ Manifesto for Maintenance Art 1969!.

While contextualized within and as art, A Critic’s Manifesto is directed toward more than just art critics. It is a blueprint for everyday life. Modigliani’s personal commitment to politics, which she weaves into her work, signals that this manifesto is a tool for managing the effects of right-wing nationalism and neo-liberal capitalism. “The true critic knows there is no formal or creative limit to what criticism can be,” she states.

Yet, the manifesto directly references photography, one of Modigliani’s primary media, in its subtitle Exposure—the act of revealing an image on a light-sensitive substrate. A diagram of a camera obscura, the first photographic apparatus, also known as a pinhole camera, reinforces the reference. This didactic illustrates how an image of an object is formed by light passing through an aperture into a black box. The correspondence between the object and the image is 1:1, except that the image is inverted.[2] Historically, photography is revered for its documentary abilities, but it is also subject to manipulation. The mutability of the medium is important to Modigliani as it is the space in which she does her work. As she writes, “the true critic is a healthy skeptic.” Skepticism prompts engagement, the crux of the manifesto, which concludes with the observation that, “In an ongoing emergency, the true critic sees that criticism is irrelevant without action.”

The first time I wrote this essay—in mid-March—it was in the vacuum that is the fraught, therefore, often inert discipline of art history. While parsing the work of Modigliani through a given theoretical lens has its merits and is, in fact, what I am trained to do, it did not do justice to the ethos of her practice, which is, as evinced in her manifesto, holistically committed to the intersection of art and politics. Art is action for Modigliani. It is a viable form of resistance. Constricting a contextualization of her work within a historical art movement like conceptualism—whether the 1970s, macho, esoteric West Coast version into which she was born or the later, more diverse, socially-minded East Coast version within she was formed—is only one way to tell her story. Modigliani calls out the myopia of art history within her own practice, which eschews a single identity. Holding degrees in fine arts and art history, she is recognized widely as both an artist and an art historian actively working “between ‘forms, authorities, politics, and genres’”.[3] The result is “simultaneously a political manifesto, a biography, an auto-biography, a fact and a fiction, and [that] cannot easily be characterized as art or scholarship.”[4] Modigliani is shamelessly fluid in a field that is traditionally, and despite all disavowal still, hierarchical (not to mention, misogynist and racist). Her shape shifting allows her to remain a “true critic” who “in fact rejects specialization.”

April 27, 1972, University of Pennsylvania (view from front)

Wood, brass, drywall, furniture, lights, paint, 2015

Photo credit: Jessica Earnshaw

Since 2014, Modigliani has been making of series of sculptures based on objects visible in press photographs of public protests during the twentieth century. She lifts the barricades, signs, and symbols from these pictures, remaking them to varying scale. Installed in the gallery space, they are out of place and out of time; yet they are not devoid of their socio-political efficacy. This work in three dimensions parallels Modigliani’s performances of re-articulated speeches. Like her sculptures, they creatively reshape history for the contemporary moment. “By adapting [these speeches], I am placing myself in conversation with a number of historical figures.”[5] Encountering her work whether as a sculpture, performance, or video, viewers are faced with history, albeit rewritten. Modigliani calls her strategy of recasting the past “critical plagiarism.”[6] It goes beyond the reverent intertextuality of feminist theorist Julia Kristeva, who considers a text to be “constructed of a mosaic of quotations… the absorption and transformation of another.”[7] Critical plagiarism helps to fulfill Modigliani’s role as a “true critic” who “recognizes that social change is a messy and imperfect affair.” Given that people are “likely to unknowingly make mistakes that will surely be discovered by others in the future,” she can right the wrongs of others from the past in the present through her work.

Thus, Modigliani’s work is palimpsest. She amalgamates different fragments into a whole not only to represent greater diversity than the original but also to critically examine its parts. Defined by the Merriam-Webster Dictionary as “writing material (such as a parchment or tablet) used one or more times after earlier writing has been erased,” palimpsest is an apt metaphor because it embodies its prior iterations, whether literally or figuratively. It affords Modigliani the ability to crisscross and collapse time.

Rome, 1947

Archival pigment print, 2020

Photography is Modigliani’s primary mode of time travel. She rejects the static understanding of a photograph as capturing the past—as something once seen to never be seen again. Like her speeches, her work revives a photograph by pulling out and altering elements within it. In her scholarship, Modigliani reads photography through performance, a framework formulated by scholar Rebecca Schneider, who considers a photograph “not as an artifact of non-returning time, but as situated in a live moment.”[8] Photography is unto itself a kind of performance of light reflecting off objects onto either a light-sensitive substrate or a digital silicon sensor comprising pixels.

Rome, 1947 (detail)

Archival pigment print

The impact of Modigliani capturing the performance of photography in her sculpture is felt within the mise-en-scène she creates in the gallery space. Her translation from photograph through performance to sculpture enlists the viewer, inviting them into the image. Like any good translator, Modigliani is not literal. She is interpretive. For Rome, 1947 (2020), Modigliani’s most recent installation, which premiered in March at Grizzly Grizzly along with A Critic’s Manifesto, she draws parallels between fascist post-war Italy and the United States today by recasting Alcide de Gasperi, Italian Prime Minister from 1945 to 1953 and founder of the Christian Democracy Party (Democrazia Cristiana), as Donald Trump. Modigliani replaces one icon with another: the receding hairline and hooked nose of de Gasperi with the orange mop and gaping mouth of Trump. Her protest sign-cum-sculpture switches de Gasperi’s monkey torso and limbs for that of a scaly alligator.[9]

Rome, 1947 literalizes palimpsest as Modigliani layers Trump onto De Gasperi. While this serves to equally demonize both men, it also points to the longstanding geo-political machinations of the United States, as De Gasperi’s leadership was marked by significant American interference. Weakened by World War II, Italy faced a great economic depression, marked by high inflation and severe shortages of food (wheat) and natural resources (coal).[10] De Gasperi, described as a pragmatic yet manipulative leader, responded with drastic monetary stabilization in fall 1947.[11] This came on the heels of the 20 September 1947 “hunger march,” a peaceful protest across Italy organized by Communists and Left-Wing Socialists. A scene from this non-violent march in Rome was documented in a press photograph that became the foundation of Modigliani’s exhibition.[12] It hangs alongside the sculptures in the gallery space, compelling the viewer to circumnavigate among the installation’s interdependent parts.

The result is an echo chamber that reverberates across both space and time. Modigliani’s Trump faces off with her second sculpture: Liberty, a near faithful recreation of a protest sign from the photograph. Tethered to a cross against a white shield, Liberty is held hostage. This grievance is evergreen, as relevant to the plight of the people under De Gasperi as it is in the United States today. Liberty’s pained expression is reflected in a mirror that hangs above Trump’s head—held by the hands of another Trump, wearing a Make American Great Again hat. The reflection of Liberty and doubling of Trump are yet again Modigliani’s subtle nods to the medium of photography. In her historical crisscross between De Gasperi and Trump, Modigliani captures the cronyism of capitalism. Like in the original protest signs from 1947 they reference, her contemporary sculptures are visual markers of speech, standing in for what can—or, sometimes, cannot—be said.

Rome, 1947 (detail)

Wood, vinyl paint, cotton, brass, plywood, mirror, linen, 2020

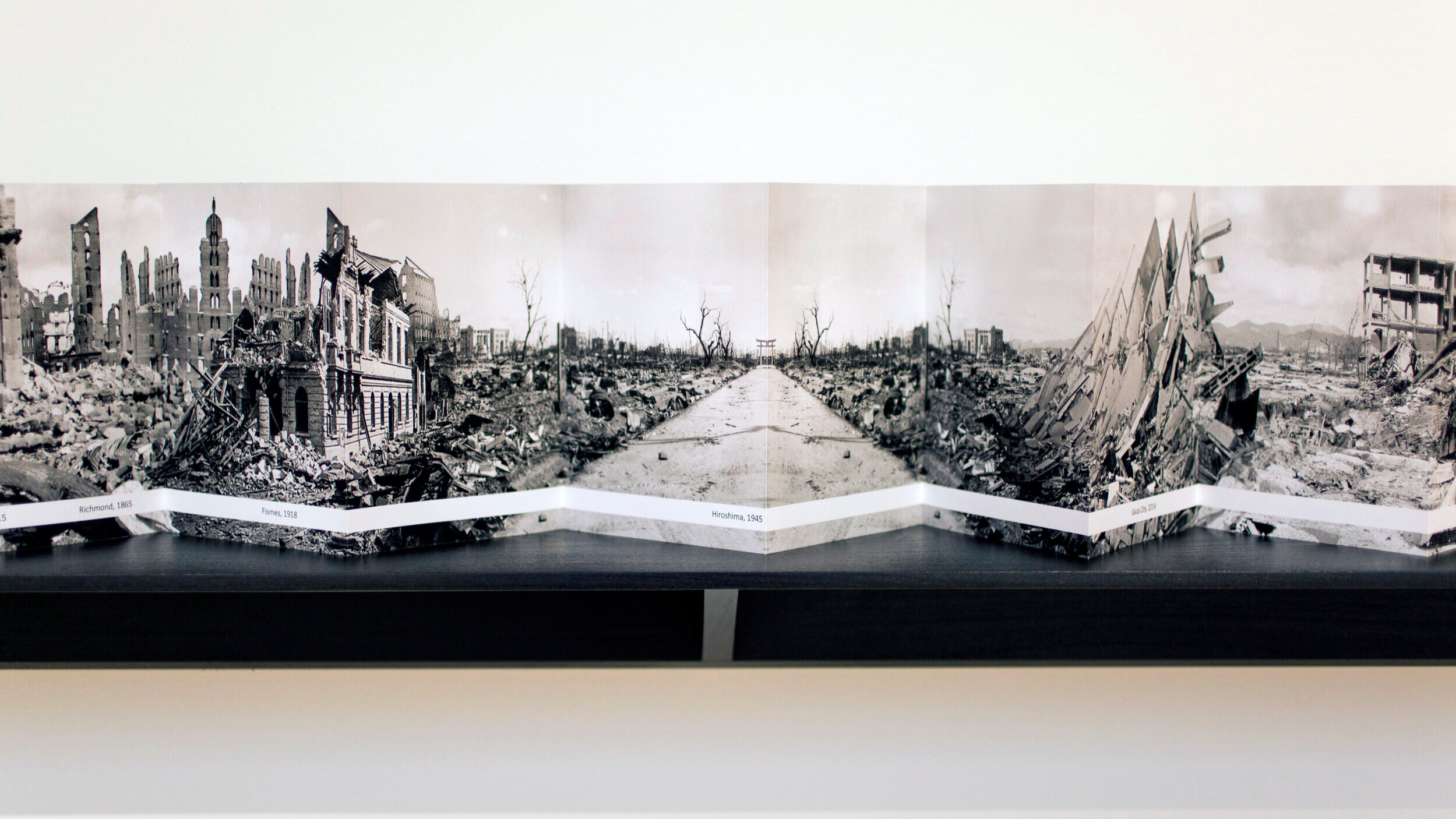

Layering seemingly disparate yet interconnected histories is characteristic of Modigliani’s practice. While an Artist-in-Residence at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in 2017, she investigated the disparate fates of two nineteenth century sculptures—William Wetmore Story’s Jerusalem in Her Desolation (1873) and G. B. Lombardi’s Deborah (1873)—both commissioned for the institution. Over the course of time, one was destroyed while the other survived but was repurposed. Modigliani’s project, entitled The City in Her Desolation, manifested palimpsest in revisiting the histories of these sculptures. Her project culminated in an accordion-style photobook that extrapolated the circumstances by which each original sculpture was destroyed. It did so by stitching together a number of destroyed urban landscapes from Richmond, Virginia after the Civil War to Aleppo, Syria in the midst of the ongoing Syrian Civil War.

The City in Her Desolation (detail)

Archival pigment print on rice paper, bookbinding, 2017

Photo courtesy of the artist and Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts

In late April, a few weeks after I first wrote this essay, I rewrote it, meditating on how the installation Rome, 1947 opened in the United States on Friday, March 6, 2020 while, halfway around the globe, Italy was on the eve of lockdown in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic. While this virus was surely in our midst at the time, its virulent effects were not as visible, as we gathered in celebration throughout the narrow hallways and one-room galleries of the 319 Building in Philadelphia’s Callowhill neighborhood. The exhibition was open for a little over a week before it was closed. The context for the exhibition was radically changed.

The effects of COVID-19 on Rome, 1947 were personal for Modigliani. Her father was born and raised in Italy, and his entire family lives in Rome’s historic city center. The artist received news of their quarantine, just as this exhibition opened. Rome, 1947 was prequel to a new project Modigliani was scheduled to begin in Rome this summer. These plans, much like this essay, changed drastically. As we continue to live in our quarantine bubbles, the future of everyday life with COVID-19 remains uncertain.

The third time—yet a few more weeks later—I came back to the essay after the murder of George Floyd and the subsequent nationwide protests against police brutality and the systemic racism that reached communities across the globe. These protests stand in stark contrast to the vehemently self-centered anti-lockdown protests of mid-April 2020, which erupted in Michigan, Ohio, Kentucky, Minnesota, North Carolina and Utah. Even in the face of a pandemic, the effects of the protests for Black lives outweigh the risks.[13] They continue as I finally finish this essay in the heat of what will be a difficult and most unforgettable summer.

In closing, I would like to reiterate that Modigliani’s sculptures are viable. Rome, 1947 harnesses the socialist spirit of collective action—beyond its textbook theories—in its use of materiality. It invites us to brazenly reject the sacredness of art and short circuit its inertia. If the gallery were open, the sculptures could be taken out into the streets. For now, Modigliani’s work remains steadfast as a truly socially-distanced protest.

Rome, 1947 (installation view)

Wood, vinyl paint, cotton, brass, plywood, mirror, linen, 2020

[1] This and the following quotations citing the qualities of a “true critic” are from Leah Modigliani, A Critic’s Manifesto: Exposure, Vol. 1 (March 2020).

[2] My interpretation of the camera obscura joins legions, including that of Jonathan Crary, who, in Techniques of the Observer: On Vision and Modernity in the Nineteenth Century (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1990), argues that it was used for determining objective truth and Kaja Silverman, who, in The Miracle of Analogy or The History of Photography, Part 1 (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2015), argues the opposite, understanding the photographer and viewer as one in the same. The latter gives the photographer/viewer greater agency and also implicates her across disparate spaces and times encapsulated by the process and product of photography. In my conversations with Modigliani throughout spring 2020, she repeatedly cited the importance of Silverman on her work.

[3] Unpublished interview between Laurel V. McLaughlin and Leah Modigliani

[4] Leah Modigliani, “Critical Plagiarism and the Politics of Creative Labor: Photographs, History, and Reenactment,” Mapping Meaning: The Journal, Issue 3 (Fall 2019): 88.

[5] McLaughlin and Modigliani.

[6] Modigliani, 88.

[7] Julia Kristeva. “Word, Dialogue and Novel,” in Leon Roudiez, ed., Desire in Language: A Semiotic Approach to Literature and Art (New York : Colombia University Press, 1980), 66.

[8] Rebecca Schneider, Performing Remains (New York: Routledge, 2011) as cited in Modigliani, 91.

[9] The original sign’s use of a monkey’s body reads as a racist reference–the exact motivation of which I do not know.

[10] “Memorandum of Conversation, by the Appointed Ambassador to Italy” (January 6, 1947), Document 543, “Foreign Relations of the United States, 1947, The British Commonwealth; Europe, Volume III,” Office of the Historian, accessed 1 April 2020, https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1947v03/d543.

[11] For descriptions of de Gasperi, see John Lamberton Harper, America and the Reconstruction of Italy, 1945-1948 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), 59. For a play-by-play account of the economic changes in Italy between 1946-1947, see Martinez Oliva and Juan Carlos, “The Italian Stabilization of 1947: Domestic and International Factors” (2007), Institute of European Studies - University of California, Berkeley, accessed 3 April 2020, https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/16396/1/stabilization1947.pdf

[12] Italian Leftist Rally Peacefully,” The New York Times (September 21, 1947), accessed 20 April 2020, https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1947/09/21/issue.html

[13] See Michael Powell, “Are Protests Dangerous? What Experts Say May Depend on Who’s Protesting What,” The New York Times, 6 July 2020, accessed 13 July 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/06/us/Epidemiologists-coronavirus-protests-quarantine.html

Leah Modigliani is Associate Professor of Visual Studies at Tyler School of Art and Architecture. She is an artist and scholar who rejects specialization in favor of a rich intellectual and creative engagement with many disciplines including fine arts, art history, critical theory, cultural studies, geography, and anthropology. Her projects arise from a set of ongoing concerns that include the history of the avant-garde and its relationship to political critique, feminist art and writing, social dissent since 1968, the history of photography, performance and re-enactment as political strategy, and the pernicious effects of neoliberal capitalism.

Modigliani's visual work has been exhibited at many galleries and museums including Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts Museum (Philadelphia), Yerba Buena Center for the Arts (San Francisco), Colby College Museum of Art (Waterville, ME), the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia (Halifax), the Museum of Contemporary Canadian Art (Toronto). Her critical writing can be found in journals and magazines such as Mapping Meaning the Journal, Anarchist Studies, Prefix Photo, Art Criticism and C Magazine. Her book, Engendering an avant-garde: the unsettled landscapes of Vancouver photo-conceptualism, was published by Manchester University Press's Rethinking Art's Histories series in 2018.

Ksenia Nouril is the Jensen Bryan Curator at The Print Center, a 105-year-old non-profit institution in Philadelphia dedicated to expanding the understanding of photography and printmaking as vital contemporary arts. A specialist in global contemporary art, Ksenia previously held a Contemporary and Modern Art Perspectives (C-MAP) Fellowship in the International Program at The Museum of Modern Art, New York. She has organized exhibitions at the Bruce Museum, Lower East Side Printshop, MoMA, and Zimmerli Art Museum. Ksenia lectures widely and frequently writes for international exhibition catalogues, magazines, and academic journals, including ARTMargins Online, The Calvert Journal, Institute of the Present, OSMOS, and Woman’s Art Journal. She has published two books: Art and Theory of Post-1989 Central and Eastern Europe: A Critical Anthology (co-editor and contributor, MoMA, 2018) and Ilya Kabakov and Viktor Pivovarov: Stories About Ourselves (editor and contributor, Rutgers University Press, 2019). Ksenia holds a BA in Art History and Slavic Studies from New York University and an MA and PhD in Art History from Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey.